Voted the Best Place to See by Condé Nast Traveler.

Suzanne Findlen Hood is the curator of ceramics and glass at Colonial Williamsburg. Her research focuses on ceramics owned and used in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century America with a particular emphasis on archaeological ceramics, Chinese export porcelain, salt-glazed stoneware, and British pottery. Her most recent exhibition, China of the Most Fashionable Sort: Chinese Export Porcelain in Colonial America, is currently on view at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum in Colonial Williamsburg. As part of Drayton Hall’s 2016 Distinguished Speakers Series, Ms. Hood’s presentation of the same title will show how a decorative arts perspective broadens the stories archaeology can tell by highlighting one of the largest groups of artifacts recovered from Colonial America archaeological sites: Chinese Export Porcelain.

First crossing the Atlantic with the settlers at Jamestown, this porcelain was a valuable commodity that served not only as a symbol of the society the settlers had left behind, but of the wealth and status of those who owned them. Using archaeological evidence, Ms. Hood will bring complexity and nuance to the curatorial understanding of the Chinese porcelain that was present in the colonial South. Within this context, her presentation on October 15th will include images of Charlestonian examples of pre-Drayton and Drayton owned pieces, which are now housed in the Drayton Hall Archaeological and Museum Collections as well as private collections. Also, objects from the Drayton Hall Collections that correspond with Ms. Hood’s presentation will be on display in a small pop-up exhibit.

Ms. Hood holds a B.A. in history from Wheaton College in Massachusetts and an M.A. from the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture and the University of Delaware. Prior to her arrival at Colonial Williamsburg in 2002, she was employed at The Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She is co-author with Janine Skerry of Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America, winner of the American Ceramic Circle Book Award for 2009.

The Fall 2015 issue of Charleston Style & Design features a thoughtful interview with Ms. Hood in advance of her presentation — don’t miss it!

In the meantime, please enjoy these images from her curated exhibit:

1. Teacup (partially reconstructed), Jingdezhen, China, 1685–1710, hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue. Excavated from the site of the Governor’s Palace.

This teacup, one of a pair recovered from the site of the Governor’s Palace, was likely owned by Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood, who served in Virginia from 1710 until 1722. In 1716, he was the first to reside in the Governor’s Palace. These teacups are ornamented over the exterior surface with a simplified version of the Sanskrit character “om,” which also appears on the bottom of the interior. Sanskrit, a liturgical language used in Hinduism and Buddhism, appears on a number of Chinese porcelains produced for over three centuries in Southeast Asia and India. The design can be read like a prayer wheel; as the bowl is rotated, the prayer is released. Despite their apparent lack of connection to a Western audience, sherds from a similar bowl were excavated at Santa Elena, on Parris Island, South Carolina, from a 16th-century colonial Spanish settlement. Two almost identical teacups were recovered from two 17th-century sites: Jamestown Island, and Bacon’s Castle in Surrey, Virginia. It seems unlikely that North American consumers knew of the connection between the decoration on their teacups and eastern religious practices.

2. Yonge Beakers.* Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1720, hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue. Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The fascination with Chinese porcelain was as strong among the Lowcountry elite as it was with the British gentry. Trade laws of the day mandated that Chinese and other imported goods be moved through a British port before their re-shipment to America, but the resulting additional cost did not dissuade affluent colonists. South Carolina planter and political figure Francis Yonge may have been the first owner of these Chinese export beakers. Although Yonge resided in an Ashley River house of modest size, he went to England several times on the colony’s business. Both his travels and his wealth gave him access to such luxury goods.

Beakers were likely used for the consumption of hot beverages such as chocolate. The form was popular in the early 18th century, but soon gave way to the shorter cups associated with tea and coffee. As a result, beakers are seldom encountered on American archaeological sites.

*Fragments of two vessels from the same set are mounted to resemble a single beaker.

3. Teacup and Saucer, Jingdezhen, China, 1722-1750, hard-paste porcelain. Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation.

These delicate tea wares were probably part of the first generation furnishings at Drayton Hall Plantation, which was finished in the late 1740s. The vessels are finely potted and of the higher quality more commonly associated with Chinese porcelains destined for the English and Continental European markets. Although not unknown in colonial America, Chinese porcelain with such minutely detailed painting was relatively rare. The superiority of these goods is in tune with period observations about the luxurious furnishings seen in the homes of the Low Country’s leading citizens.

These pieces were part of a larger group of cups and saucers that may have included a matching teapot. However, it is just as likely that they were used with a teapot made of silver, white salt-glazed stoneware, or another material. Mixing different wares was quite acceptable, even in gentry settings.

4. Saucer Dish, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1750, hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue. Museum Purchase, The Buddy Taub Foundation, Dennis A. Roach and Jill Roach Directors, 2013-29.

Porcelain decorated with cobalt blue had been popular since the 14th century when the Chinese first developed it. The main source of cobalt at that time was Persia, where there was a thriving earthenware industry. Because cobalt can be fired to a very high temperature in the kiln without burning off the dish, it had an economic as well as an aesthetic advantage: cobalt-decorated pieces of porcelain were not only beautiful, they also did not have to undergo multiple firings.

Blue-decorated porcelain appears archaeologically on many colonial sites. This fine example features a water buffalo, a popular design in colonial Virginia of which variations have been found on numerous sites. A dish with similar decoration, but rendered in more elaborate opaque enamels, was owned by Miles Brewton of Charleston, South Carolina.

5. Dish, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1736, hard-paste porcelain with opaque enamels. Museum Purchase, Wesley and Elise H. Wright in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Clay Hofheimer II and in honor of John C. Austin, 2013-57.

This dish exactly matches one owned by the Lee family of Stratford Hall in Westmoreland County, Virginia. Stratford was built in the late 1730s, which corresponds to the date of this piece. The example recovered at Stratford was found in a rat’s nest in a wall of the house during 20th-century restoration. This pattern was popular on export porcelain in this color palette as well as in translucent enamels called “Imari.” Imari versions have been found archaeologically in Williamsburg and are also known in the Gore and Cargill families of Massachusetts. The design depicts two crabs holding a Chinese coin between them. The colonists who dined off of these wares probably did not know that, to a Chinese audience, the design indicated wishes for prosperity and financial success.

6. Cream jug, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1735, hard-paste porcelain with translucent enamels. Museum Purchase, 1964-335.

As the market for porcelain grew in Europe, potters in China began to produce more wares specifically based on Western shapes. This cream jug directly relates to silver prototypes, while the decoration continues to be Asian in inspiration. This piece descended in the Glen-Sanders family. It may have been owned by Deborah Glen and her husband John Sanders who married on December 6, 1739. Both the Glen and Saunders families were prominent in colonial New York. The cream jug was most likely used at the family home, Scotia, near what is now Schenectady.

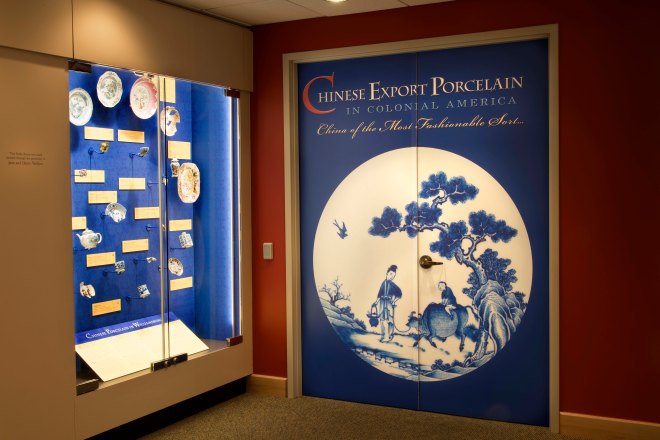

China of the Most Fashionable Sort: Chinese Export Porcelain in Colonial America, DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. (View 1)

China of the Most Fashionable Sort: Chinese Export Porcelain in Colonial America, DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. (View 2)

China of the Most Fashionable Sort: Chinese Export Porcelain in Colonial America, DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. (View 3)

To learn more about the exhibit and the art museums of Colonial Williamsburg, please follow these links:

www.colonialwilliamsburg.com/do/art-museums/wallace-museum/chinese-porcelain/

www.history.org/history/museums/

www.facebook.com/ArtMuseumsofCWF

Doors open at 5:30pm with a Wine and Cheese Reception.

Presentation starts promptly at 6:30pm.

No advance reservations; please arrive early as seating is limited.

Sponsored by The Francis Marion Hotel, Charleston, SC.https://francismarionhotel.com/